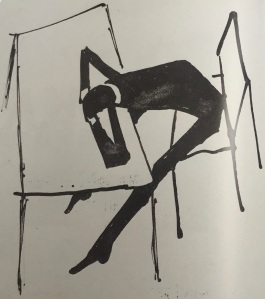

This truly is an iconic drawing: often interpreted as an image of either Kafka’s despair at the grind of life, or his exhaustion after spending the night hours feverishly capturing the products of his imagination. It could also be said to accurately reflect my own brain-ache when studying Kafka’s novels at university. Traces of the resulting scars remain and yet, I find myself fascinated. Not by the novels – I feel no urge to revisit them – but by the man. When you think of it, it truly is amazing. Kafka died 100 years ago today, having published relatively little. (2 short story collections, Betrachtung / Contemplation (1912) and Ein Landarzt / A Country Doctor (1919), with the novella Die Verwandlung / Metamorphosis (1915). As a writer he was well known in regional circles, but certainly not the global superstar he is today. Just how did this happen?

That is precisely the subject of Kafka: Making of An Icon, published by Bodleian Library Publishing to coincide with a special exhibition that runs to 27.10.24. I’m trying desperately to wangle a trip, but not sure I can pull it off. In the meantime, however, I shall content myself with this lavish and extremely informative catalogue. Consisting of eight essays from 7 different contributors, and edited by Ritchie Robertson, a former German lecturer at Oxford, the book begins by posing the question: what was Kafka’s nationality? The underlying complexity to that answer being perhaps the first clue to the complicated human that Kafka became. Some essays focus on Kafka in the real world; his upbringing, his relationships with fellow authors, his love life. A fact that always takes me by surprise is how much this tortured human was valued as an employee – even if he hated the job of insurance assessor, (you know, the job that had him slouching over his desk in despair) he was good at it. To the point that he was deemed an essential employee and, therefore, exempted from military service during WWI. Other essays focus on his creativity: his drawings, the novels, the short stories, providing insights into how real life may or may not have influenced them, Kafka’s techniques.

Chapters 7 and 8 tell the story of Kafka’s afterlife. In theory there shouldn’t have been one. He did tell his friend Max Brod to destroy all his unpublished papers. The question here is did he mean it? (Cf James Hawes Excavating Kafka). Fortunately or unfortunately (whatever your viewpoint), Brod disobeyed those instructions, edited and published many of Kafka’s works, and the rest they say is history. Although not everyone is thrilled at what he did. One snippet in chapter 7 about how the individual chapters of The Trial were in separate notebooks (pamphlets) with no clues as to their chronological sequence. What we read today is Brod’s interpretation. (Now this might just persuade me to take another look at The Trial … possibly, maybe ….)

Chapter 8 entitled Kafka’s Global Afterlives takes a look at how Kafka has progressed from a relatively unknown into a global brand. Shrewd (saturated?) marketing in Prague where no tourist can escape his presence, adaptations of his works to other media, film, opera, sculpture, the list is comprehensive. Not quite endless, but I have a feeling that in this centenary of his death, that milestone may in fact be reached.

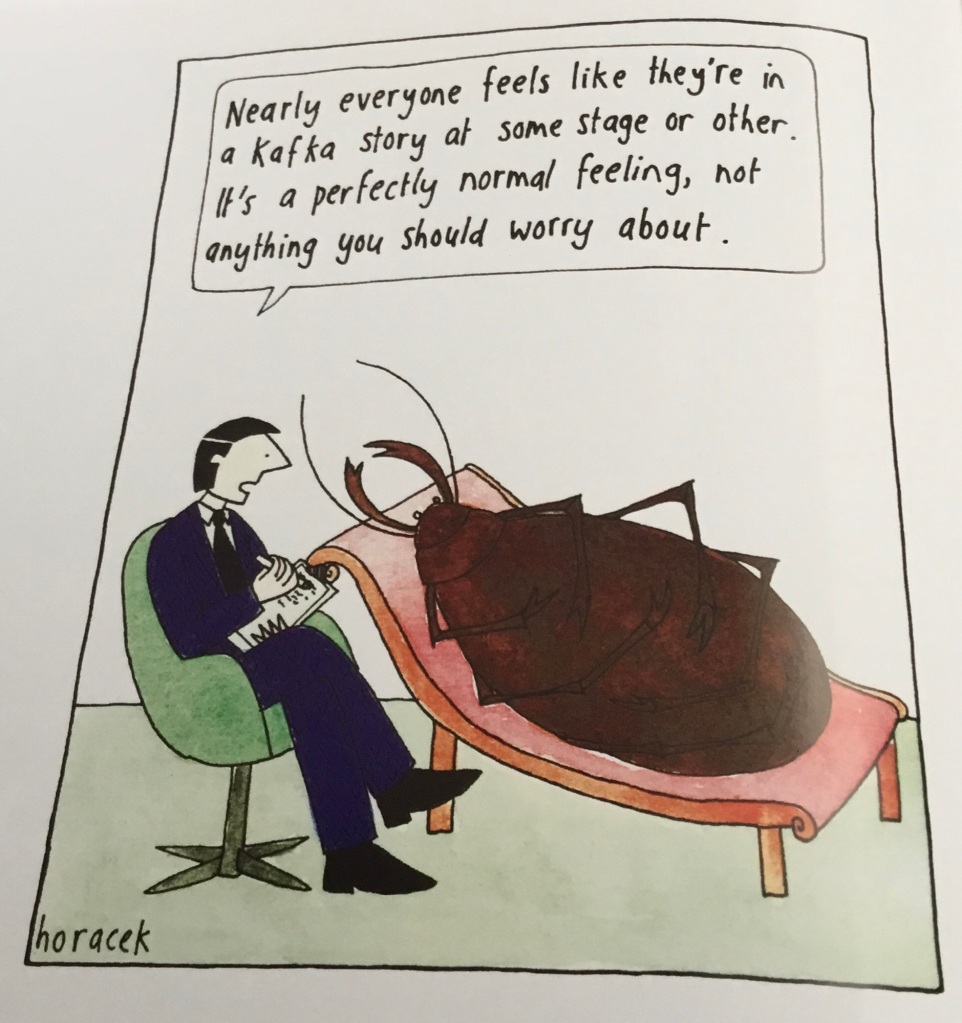

But what is it exactly that accounts for the world’s appetite for all things Kafkaesque? Judy Horacek’s cartoon summarises his universality perfectly:

In fact, I think her cartoon nails the reason why I didn’t take to Kafka all those years ago. I was too young, all was proceeding to plan, my universe not yet knocked off kilter. 45+ years later, perhaps I’ll get it now. Well, 2024 is the year my #krazyaboutkafka reading project will answer that question for definite. Will Kafka continue to drive me krazy or will I become a bona fide krazy fan? Time will tell.

Kafka: The Making of An Icon was a superb choice to kick off this project. At £35 though, it is a tad expensive, and I was fortunate enough to receive a review copy. Those seeking a more modestly priced introduction to the author may like to seek out Ritchie Robertson’s Kafka: A Very Short Introduction or James Hawes superb Excavating Kafka.

Or access the wealth of information available on the Goethe Institute website for free!

Luckily for me I can get to this exhibition as it’s local because it does sound fascinating and like you it’s the man I’m interested in, but then again may be I’ll be tempted to try reading him again. . .

LikeLike

It’s a superb book isn’t it? Not cheap, as you say, but I thought the contents were stunning, and they’ve certainly made me want to go off and re-read Kafka!

LikeLike

I’m glad it wasn’t just me suffering brain-ache as a young undergraduate while reading Kafka. His novels just seemed to exacerbate my existing Angst at the time. I wouldn’t go back to them now, but I am interested in his status as a cultural icon and would definitely visit the exhibition if I got a chance to visit Oxford before the end of October. I’m going to try to watch the German ARD series on Walter Presents, though, hoping it’s Kafka lite. Thanks for the info about the exhibition and catalogue.

LikeLike

I’m two episodes into the series. It’s very good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kafka is obviously the author to read this year. Fascinating character. I recently read Metamorphosis which is really a weird piece. I hesitated long since I don’t like insects, and sometimes it came over me. But, it was an interesting take on life. I read The Trial many years ago, but don’t remember too much. Maybe a re-read this year.

LikeLike